UK primary school children being left in the dark?

By Graeme Shaw, Technical Director at Zumtobel Group

The Institute of Education found that the quality of our primary school years is more important on academic progress in later life than gender or family background.

An incubator for the next generation of leaders, thinkers and innovators, the environment in which we learn has been evidenced to affect motivation, happiness, achievement and success of students.

Which begs the question why there is not more focus on our learning environments.

Within our current school systems (designed by politicians), teachers are forced to spend the majority of their time focussing on the preparation and drilling of children for tests, an approach that is squeezing the creativity and joy out of learning, at the expense of all else.

Primary students spend over 7,000 hours at school (by the end of their 6th grade), most of which in a single classroom designed before the development of dynamic lighting and digital technologies such as smart boards and tablets.

In the past (and even present) teachers have been known to use workarounds to overcome poor lighting (known to cause headaches, eyestrain and fatigue), hanging light shades of varying colours over fluorescents to try and create the best learning environment for their students.

While we may have a newfound appreciation for education settings – sparked by the pandemic, remote learning and the pain of juggling teaching alongside working from home, most are still unaware of the significant underfunding in the sector.

Cuts that have led to half of all public school teachers nationally seriously considering leaving the profession[1] due to underfunded dilapidated school buildings, crowded classrooms and poor pay.

While there are admittedly bigger problems – run-down school buildings which in some cases are structurally unsound, the good news, for the buildings we can save, is that simple changes in how we light our classrooms can bring significant benefits – beyond the simple energy savings needed to navigate the energy crisis.

Graeme Shaw, Technical Director at Zumtobel Group, shares his thoughts on Government underspending and how good lighting can improve our early years learning, concentration, engagement, health and performance!

Where are we going wrong?

Education is the second-largest element of public service spending in the UK (behind health), but it still only represents 4.5% of national income[2]. That’s in comparison to Denmark which spends 7.3 % of GDP, Sweden at 7.1 %, and Norway at 6.9 %[2].

Pre-pandemic, total spending stood at £104 billion (4.4% GDP). 8% lower than in 2010-11, when it represented 5.6%[3] with only a tiny proportion of that budget allocated to maintaining campuses (11.4%), and an even smaller proportion allocated to lighting[1].

While the Government has clearly recognised this needs to be addressed: the Prime Minister announced the School Rebuilding Programme (SRP) in June 2020, which is set to deliver over 500 rebuilds and refurbishments and provide “modern purpose-built schools designed for 21st-century learning” over the next decade. Does it go far enough?

If recent news is anything to go by. Potentially not.

The Guardian[1] recently shared that a staggering 83% of school leaders do not believe they have sufficient capital funding to maintain their buildings and facilities. With teachers complaining of leaking ceilings, broken heating, inadequate ventilation, and no money to fix problems.

The findings, from a 1,500-strong survey of leaders conducted by the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT), comes just months after a government-commissioned study found that the repair bill for state schools in England had ballooned to £11bn (including over £2.5bn for electrical and IT repairs, £2bn on “mechanical services” such as air conditioning and boilers, and £1.8bn on external walls, windows and doors).

With heads blaming a decade of austerity, the likes of which not seen in post-war UK history, Local authorities’ tight financial positions have only been exacerbated by the pandemic and that’s without adding rising energy costs into the mix.

With school budgets being hammered it’s perhaps no wonder that the Government’s focus is on saving money – which LED lighting (through energy reduction) certainly delivers. However, we believe this has led to a focus on the ‘hard environment’ – achieving ultra- efficient spaces: a focus on lux and lumens and JUST meeting the standard, while achieving the maximum energy savings. And not where it should be focussed. Lighting for the benefit of people.

Why this is wrong

Classrooms are currently designed to provide a uniform distribution of light. In the absence of natural light, or insufficient natural light a minimum illuminance of 300 lux (0.6 uniformity, UGR19 and Ra 80) is widely regarded as suitable for general tasks – designed to fulfil the requirements of BS EN 12464-1. Typically provided by recessed luminaires. But, based on what research?

The simple lighting regulation standards, which are now woefully out of date, define only the minimum task area illuminance levels, and by that, the minimum amount of light required by law – which is still very low.

Neither classrooms or the lighting within are currently being designed for the rapidly changing activities associated with the different pedagogical approaches used in teaching today.

Remember how many hours are spent within one classroom… one room – used for reading, writing, art. What the standards do not currently take into consideration are the softer aspects of lighting and the fundamental role it plays in environment creation.

Light for balanced learning and comfort

There is a growing body of research that evidences the power of connecting light and people.

In a well-lit classroom, with individual control of environmental factors, students are found to be more relaxed, not as sleepy, and more motivated to learn.

We believe there are 4 key considerations:

- Light intensity

- Uniform appearance

- Constant luminous flux in all colour temperatures

- Perfect colour consistency between systems and luminaires (MacAdams SDCM 3-4)

- Comfortable dimming

- Direction of light

- Colour

- Tunable white, with a variable colour temperature from 2700 K to 6500 K, CRI >90

- Increasing the blue component for an activating atmosphere

- Increasing the red component for a calming atmosphere

- Time

- The right atmosphere at the right time

- Artificial light complements and is subordinate to daylight

Through standard lighting we can provide visual comfort, if consideration is given to glare and contrast but with holistic integrations of lighting concepts such as:

- Limbic lighting – we can also provide emotional comfort

Light that supports dynamic learning activities by quickly adapting the atmosphere. The “polarisation of attention” as defined by pioneering educator Maria Montessori – states that playful abandon and complete immersion in the task – can be supported by environmental conditions. Positive emotions support the joy of discovering and learning, thus helping people to learn successfully.

- Limbic lighting within buildings has a holistic influence on people: physical, psychological and social

- Architecture requires user participation

- For sensory experiences (wellbeing)

- Human Centric Lighting (HCL) – we can stimulate biological responses for improved health

In addition to daylight, HCL promotes the activation and regeneration of students

and teachers. The right lighting situation at the right time supports natural physical processes throughout the day. Our inner clock is stabilised and the quality of sleep is improved. For healthy and active learning.

This is in comparison to the world-renowned Nordic education system (and some parts of the US), who spend more (higher taxation means schools are better-funded), while importantly, being less target-driven and more child-centred. Having introduced human-centric concepts such as Hygge (pronounced hue-guh not hoo-gah), which means to create an environment that helps students relax, find comfort, be together and be inspired to learn.

A concept our UK universities, as businesses, understand – as they are in direct competition with one another to attract pupils.

In the pressure to meet targets, have we therefore forgotten what a privilege – and a responsibility it is to shape the environment for our future generations?

Lighting to JUST meet a standard is not enough. Not when we know that lighting quality has a direct influence on students’ learning performance and even test scores.

The impact of classroom design on pupils learning

The former Education Secretary, Gavin Williamson recently stated that: “The environment children are taught in makes such an enormous difference to their education”[4].

So, what do good ‘modern purpose-built’ classrooms look like?

Perhaps the most relevant research in this area is the Sin Paradigm (which stands for naturalness, individuality and stimulation) by Professor Peter Barrett, which studied the connection between the physical design of primary schools and academic progress.

The study[5], dating back to 2013 (but still very relevant today), of 153 classrooms, 27 schools and three and a half thousand pupils focussed on 7 key design parameters: Light, Temperature, Air Quality, Ownership, Flexibility, Complexity and Colour. It found that the impact of building design, especially light, temperature and air quality has a significant impact, around 50%, on pupils’ learning outcomes.

What we know

Children’s eyes let in more light than adults, are more permeable to both ultraviolet and blue light, and are more sensitive to glare.

Children have higher sensitivity to light because they have smaller pupils and less melatonin suppression than adults, affecting their sleep/wake cycles and circadian rhythm (our 24-hour internal clock).

Cases of myopia (short-sightedness) have more than doubled in the past 50 years and now affect one in six children in the UK by the age of 15. Most likely to occur between the ages of 6 and 13, more research is needed on why we’ve seen such a significant increase, however, it is believed to be the environment; children spending more time indoors, on screens and reading (mainly black writing on a white background) and not getting enough daylight is to blame.

Studies conclude that exposure to blue-rich light, especially during morning sessions, increases academic performance, concentration and progression of students. While warm lighting can reduce aggression and positively affect social behaviour.

Higher red-spectrum proportion and dimmed room lighting create a calm and private space. This ambience also supports reading aloud sessions, prayers, mindfulness breaks and communication.

While violet to azure (similar to natural sunlight), reduces eye strain, is supportive of circadian entrainment and increases the melanopic content of the light

Field research includes:

A study by Heschong Mahone[7], which found that students in well-lit classrooms with more daylight/bigger windows progressed approximately 20% faster in maths and reading. As we know, daylight produces biological effects on the human body (Wurtman, 1975).

Hathaway (1990)[9]. argues that there is a correlation between absenteeism and lighting. He goes on further than any other researcher, to make links to lighting and incidences of dental cavities and even gains in height and weight. His study found that students under high-pressure sodium vapour lamps had the slowest rates of growth and development as well as the poorest levels of attendance and achievement.

Jago & Tanner argue that ‘the visual environment affects a learner’s ability to perceive visual stimuli and affects his/her mental attitude, and thus, performance’ (1999)[9].

Differences in performance and mood under different kinds of lighting in relation to gender and age were studied by Knez and Kers (2000).

Benya suggested that for ‘lighting to be effective, daylight must be supplemented by automatically controlled electric lighting that dims in response to daylight levels’.

(2001). Supported by Barnitt in 2003.

There is evidence that children read more fluently in classrooms that are very brightly-lit (Mott et al 2011; Mott et al 2014). Kids may perform better on mathematics tests, too (Choi and Suk 2016).

In 2019, a Californian pilot[6] to replace costly, inefficient fluorescent lighting in classrooms in a bid to save energy, found that adjustable white LED lighting (which allowed the teacher to control the colour and intensity of the classroom lighting) improved the learning environments, with observed improvements in student behaviour, within both traditional and special needs classrooms.

More recently, we worked with the University of Aalborg and partners to implement an advanced lighting concept at Herstedlund School, in Denmark.

Using a lighting management system (LITECOM) to collect data on the use of light in the classrooms over a three-month period. The findings made for interesting reading.

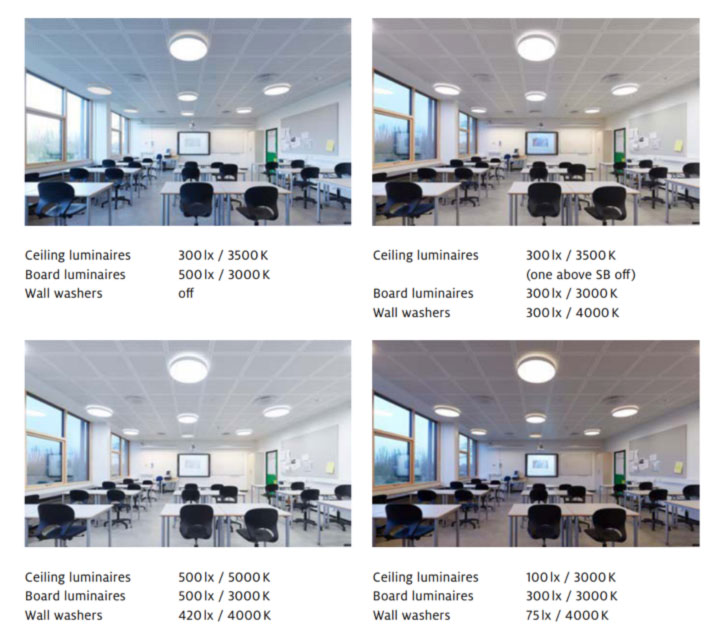

The internet-enabled and app-based lighting management system meant that four pre-programmed lighting scenarios could be easily controlled by the teachers. We worked with the teachers to design different environments for different learning processes. The colour settings and light intensity of all the luminaires in the classroom were individually adjustable, whilst teachers could also define their own settings.

The lighting scenarios were designated as follows: Standard, Smart Board, Fresh and Relax. Which you can see below.

Five motivations for using lighting as a tool to support teaching were identified:

- Supporting and structuring learning activities – promoting interaction between students and teachers

- Communicating through lighting and involving students (for example using the Relax scene while reading)

- Influencing the activity level and behaviour of students

- Creating atmospheres – teachers chose lighting scenarios and adjusted the lighting to support activities and structure lessons

- Helping with the completion of visual tasks and boosting visual comfort

The findings of the study demonstrated how the visual effects related to comfort and visibility play a key role in both the teachers’ and students’ sense of well-being and satisfaction.

Summary

Behind educators and families, the physical environment (including daylight and artificial lighting within) hold the potential to influence how successfully our children learn – and should therefore be seen as a third educator. Receiving a greater level of funding, research and importance.

Children should not have to adapt to the environment, the environment should adapt to the child. But for this to be successful, a paradigm shift in policy and focus will be required.

Our classroom crisis can be solved if we can rapidly transition ministers away from their obsession with meeting targets and provide the funding the sector so desperately needed.

While lighting does account for the greatest proportion of energy costs in schools, good design, specification, management and controls, can have a significant impact on limiting electricity consumption, saving energy, keeping running costs to a minimum and providing the nurturing environment our children need.

Meaning that sustainability commitments, such as net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 are still achievable, but alongside solutions that also benefit our health and well-being.

We can and absolutely should use lighting as a supplementary tool to support learning activities, to help student/teacher communication and to positively affect students’ activity levels and behaviours.

Our call to action

Light not just to meet lighting standards within a room but light in alignment with users’ needs. To create atmosphere. To support visual tasks. To create classrooms that are fit for the 21st century.

As teachers become learning companions/guides, it is the progressive schools that provide rooms that adapt to individuals and the time of day, and that support new pedagogical/educational concepts that will win.

A concept supported by Dr Shelley James, Founder of The Age of Light Innovations, Consultant and WELL advisor, who commented:

“British children will spend an average of 23 hours per week on screens (19 minutes every day10) – compared to just four hours per week outside11. One in five of children will not go outside today at all.”

This, interestingly, is less time than UN guidelines for prison inmates – which states a minimum of one hour of suitable exercise and fresh air daily12.

“Exposure to the right light at the right time is therefore crucial to shape a child’s development and their long-term health and well-being – from the likelihood of becoming blind13 or developing diabetes14, to their ability to switch effectively between tasks15 – and even to manage risk16.

School is not a panacea and lighting is just one component of a healthy learning environment, however as this article points out, children spend many hours of their young lives in a classroom – given the private rate of return for one extra year of schooling is around 9% every year17 – any investment is money well spent”.

We must not forget that decisions made today will shape the world of tomorrow.

CLICK HERE TO VISIT THE ZUMTOBEL WEBSITE

References

- https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/aug/28/england-schools-in-urgent-need-of-repairs-say-heads

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Educational_expenditure_statistics#Overall_educational_expenditure

- https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15858

- https://www.paulhowell.org.uk/news/second-round-prime-ministers-transformative-school-rebuilding-programme-launched

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132315000700#bib1

- https://www.pnnl.gov/news-media/led-lighting-saves-money-and-helps-autistic-students

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17508975.2015.1087835

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220671.1995.9941304

- https://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/18471/1/SCRI_Report_2_school_design.pdf

- https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/covid-19-lockdown-measures-and-childrens-screen-time/

- https://www.childinthecity.org/2018/01/15/children-spend-half-the-time-playing-outside-in-comparison-to-their-parents/?gdpr=accept

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/25/three-quarters-of-uk-children-spend-less-time-outdoors-than-prison-inmates-survey

- Landis EG, Yang V, Brown DM, Pardue MT, Read SA. Dim Light Exposure and Myopia in Children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018 Oct 1;59(12):4804-4811. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24415. PMID: 30347074; PMCID: PMC6181186.

- https://www.sleepfoundation.org/physical-health/lack-of-sleep-and-diabetes

- https://news.feinberg.northwestern.edu/2022/03/exposure-to-artificial-light-during-sleep-may-increase-risk-of-heart-disease-and-diabetes/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20results%20from%20this%20study,The%20Ken%20and%20Ruth%20Davee

- https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/SC21/SC21031FU1.pdf

- https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29672

Other reading

https://resourced.prometheanworld.com/education-system-deep-learning/

https://pdkpoll.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/pdkpoll51-2019.pdf

https://www.zumtobel.com/com-en/limbic-lighting.html

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132315000700

https://www.zumtobel.com/PDB/teaser/SV/Study_Education_and_Science_Sonthofen.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360132321007873

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!